As with all kinds of waste in a globalizing world, figures for food waste are overwhelming – take a global total of 1/3 of all food produced in 2021, for instance[i]. This waste isn’t a necessity for feeding the planet, for ensuring food security, for keeping malnourishment at bay, it’s a direct consequence of the profit-making structures of the global food regimes which over-supply zones of wealth and malnourish poorer zones.

First and last, this is a waste-dependent system; the more profit you make through a corporate food production system, the more waste you create – profit increases waste, waste supports profit.

Neither is the waste just discarded food. The ripple effects of food and the waste produced through these systems are enormous, from the 70% of naturally-extracted water they use (and so at least 1/3 of that is wasted) to producing 1/3 of carbon emissions globally, to wasting fuel and oil used to transport wasted food, to wasting land used for producing wasted food.

Again, these aren’t necessary losses for the production of vital food, they’re systemic losses from producing profit-maximizing food cheaply on a global scale; the global spread of a cost-reducing food system increases waste. The global scale of production, distribution, sale and waste is directly related to income, as well.

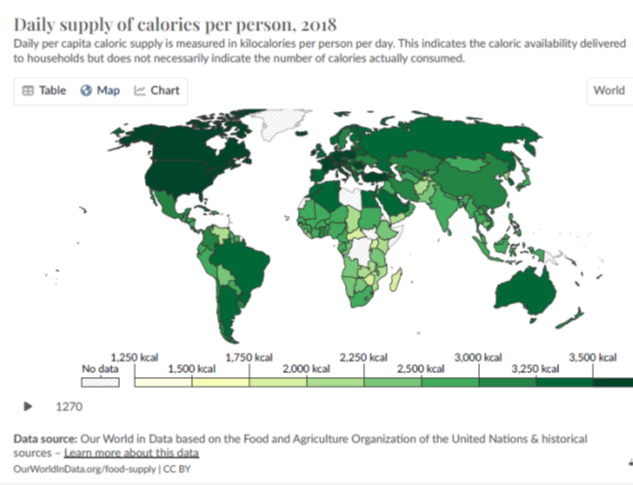

As you can see on the diagram below, low-income countries of the Global South that produce massive amounts of consumable goods for richer countries, are those with the lowest calorific consumption. The country with the lowest calorific consumption is Ethiopia, one of the most important producers of coffee in the world:

(Sources: www.ourworldindata.org/food-supply-kcal; www.obesity.procon.org/global-obesity-levels/ and https://www.howtocook.recipes/top-20-countries-that-eat-the-most-and-least-calories-per-person-each-day/ )

But looking at facts and figures of waste (direct or indirect) doesn’t tell you much about the global systems that produce it, how people are trapped into systems that both malnourish at one end, then over-feed at the other

ETHIOPIA, COFFEE WASTE AND STARVATION

Ethiopia’s coffee is a great example of how massive waste is created for the provision of the smallest amount of a luxury product – since 1965, global consumption of coffee has increased from just over 60 million bags a year in 1965 to 166.63 million bags in 2020/2021[i].

Of all of this coffee, less than 1% of any coffee bean is consumed; nonetheless, 25% of the population of Ethiopia is directly or indirectly employed in the coffee sector and the country is the 5th largest producer in the world[ii].

In 2022 exports from Ethiopia were overwhelmingly agricultural – with coffee, tea and spices at the top (49.4% of total exports). Even during drought years, the crop production index for Ethiopia shows a substantial increase in agricultural production[iii] – between 2010 and 2019 land under coffee production increased over 97%[iv].

At the same time, Ethiopia is dependent on food aid to meet basic consumption needs, even as farming inefficiency internally wastes a lot of the country’s own food production, including some 40% or more of tomatoes, papayas and mangos[v].

The country has been dependent on annual food aid since 1980, so that even when harvests are good, millions of tons of food are required. By 1985 Ethiopia was already locked into a drought-war-famine-emergency feeding cycle:

“”there is little chance of breaking the constant cycle of drought-famine-emergency feeding.” Drought and fighting have destroyed fodder grass, and erosion is occurring “on a catastrophic scale.”[vi]

Ethiopia, locked into a food aid system which is exploited by the country’s elites, continues to lose agricultural land through soil degradation, drought etc. – GDP loss from reduced agricultural productivity is estimated at $130 million per year[vii]. So, Ethiopia loses productive agricultural land at the same time that production of coffee increases, export earnings from coffee increase and more small farmers (15 million) are dependent on coffee[viii][1]. Ethiopia is both Africa’s biggest exporter of coffee and the most dependent on food aid!

The irrelevance of the trade in coffee to the welfare of the Ethiopian people is horrendous:

In 2017 Ethiopia suffered a massive drought in which some 23 million people across Ethiopia, Kenya, Somalia and South Sudan were left in urgent need of food, water and medicines. By July of 2017, however, Ethiopia earned ‘a record $866 million from the export of coffee’[ix]; record coffee earnings throughout a horrendous drought – how can that be possible?

In 11 months from 2021/2022 Ethiopian coffee exports earned a record US$ 1.1 billion, despite the drought of 2022. At the same time, the number of people with insufficient food in Ethiopia reached a peak of 26.3% of the population by April 2022[x]. Across the South and South-East of Ethiopia, including the coffee-producing province of Sidamo, coffee earnings rose strongly as malnutrition accelerated everywhere.

Ethiopia is almost completely dependent on an artificial system of food dumping[xi] by rich highly-subsidized economies of wealthy countries (the US, EU), a corrupt food dumping system controlled by Ethiopian elites which is used for profit and maintaining the military.

At the same time, luxurious, waste-driven coffee exports increase elite profits, as indigenous agriculture plunges downwards…

THE US – AN OBESITY-PRODUCTION SYSTEM DEPENDENT ON FOOD WASTE

Let’s move from the country with the lowest calorific consumption to the area with the highest calorific consumption – North America. As you can see from this map produced by the Our World In Data series North America receives a higher calorific supply than anywhere else in the world and, top of the heap, the US in 2018 supplied 3,782 kilocalories per person per day. The wealthier the country, in general, the higher the average kilocalorie count:

The US is THE global summit of food use and abuse – top of the world for food imports for 2021, top of the world for food exports and second only to China in agricultural production. And one of the worst in food waste, with (depending on the source) 30-40% of food supply being wasted in a gluttony that’s getting worse and which has increased by 50% since 1970 .

Massive wealth allows the US to absorb the most food and waste most of it, in the body as well as in land-fill; the US corporate food economy depends on the acceleration of gluttony. Besides waste, healthwise this is a disaster – currently some 4 in 10 US adults have obesity and the rate is climbing . Mortality from obesity-related issues is growing, through high blood pressure (hypertension), high LDL cholesterol, low HDL cholesterol, high levels of triglycerides (dyslipidemia), type 2 diabetes, coronary heart disease, strokes and gallbladder disease.

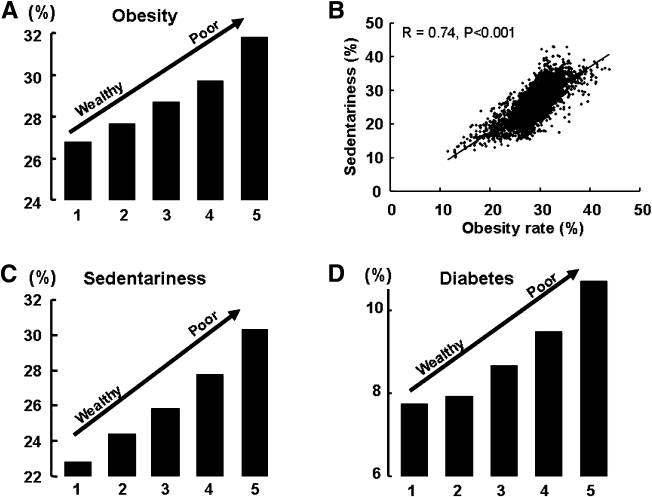

But it isn’t wealth that drives the gluttony in the US – large-scale retailers like Walmart, Target and CostCo point out the importance of low-income/SNAP (Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program) households in driving their profits. Contrary to what logic suggests, poverty in the US is a major driver of obesity!

[1] CSA (Central Statistical Agency) (2017): Reports on Area and Production of Crops (Private Peasant Holdings, Meher Season). Addis Ababa, Ethiopia

THE FUTURE OF FOOD WASTE

Globally, food waste is growing[i]. Waste is growing because of the systems that produce, store and distribute it – waste isn’t a shameful symbol of mismanagement, it’s an appropriate indicator of high turnover and high sales:

“The reality as a regional grocery manager is, if you see a store that has really low waste in its perishables, you are worried. If a store has low waste numbers it can be a sign that they aren’t fully in stock and that the customer experience is suffering. Industry executives and managers view appropriate waste as a sign that a store is meeting quality control and full-shelf standards, meaning that blemished items are removed and shelves are fully stocked (Alvarez and Johnson 2011; quoted in NDRC 2012).”

The only conclusion we can reach is not only that ‘without waste there is no value’ (Gille, 2010 [ii])but also that the financial value of food depends on the ability to control its waste. This is why Gille talks about the need not to see waste as a concrete reality, as a thing or set of things, but as ‘abstraction’.

As corporate actor/networks control more and more food production, distribution and sales globally, waste will automatically increase. As profitability from food monopolies increases and the need for more and more food products increases, so again waste will increase…

[i] Emiliano Lopez Barrera, Thomas Hertel, Global food waste across the income spectrum: Implications for food prices, production and resource use, Food Policy, Volume 98, 2021.

[ii] Gille, Z. (2010) Actor networks, modes of production, and waste regimes: reassembling the macro-social, Environment and Planning A 2010, volume 42, pages 1049-1064.

[i] Emiliano Lopez Barrera, Thomas Hertel, Global food waste across the income spectrum: Implications for food prices, production and resource use, Food Policy, Volume 98, 2021.

[i] Coffee consumption worldwide from 2012/13 to 2020/21, Statista, https://www.statista.com/statistics/292595/global-coffee-consumption/

[ii] Assefa Ayele, Mohammed Worku, Yadeta Bekele (2021) Trend, instability and decomposition analysis of coffee production in Ethiopia (1993–2019), Heliyon, Volume 7, Issue 9.

[iii] Ethiopia: Crop production index, https://www.theglobaleconomy.com/Ethiopia/crop_production_index/

[iv] CSA (Central Statistical Agency of Ethiopia) Agricultural Sample Survey 2018/2019. Volume I Report on Area and Production of Major Crops (Private Peasant Holdings, Meher Season). Statistical Bulletin 587 (2019). Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.

[v] https://www.capitalethiopia.com/2022/04/25/waste-is-expensive/

[vi] Ethiopia: The Use of Food as an Instrument of U.S. Foreign Policy, Jack Shepherd, Issue: A Journal of Opinion, Vol. 14 (1985)

[vii] AGNES. (2020). Land degradation and climate change in Africa. Policy Brief No, 2

[viii] CSA (Central Statistical Agency) (2017): Reports on Area and Production of Crops (Private Peasant Holdings, Meher Season). Addis Ababa, Ethiopia

[ix] Assefa Ayele, Mohammed Worku, Yadeta Bekele (2021) Trend, instability and decomposition analysis of coffee production in Ethiopia (1993–2019), Heliyon, Volume 7, Issue 9.

[x] https://www.statista.com/statistics/1236832/number-of-people-facing-food-insecurity-in-ethiopia/#:~:text=Furthermore%2C%20the%20prevalence%20of%20food,million%20individuals%20in%20April%202022.

[xi] Anup Shah (2005) Food Aid as Dumping, https://www.globalissues.org/article/10/food-aid-as-dumping

[i] UNEP, 26th Sept 2022, “Why the global fight to tackle food waste has only just begun”, https://www.unep.org/news-and-stories/story/why-global-fight-tackle-food-waste-has-only-just-begun#:~:text=According%20to%20the%20United%20Nations,globally%20is%20lost%20or%20wasted.